A Primer on Organizational Theory and Tapping into Human Potential

Article by Zero Mass | Edited by Hiro Kennelly

Welcome to Bankless Publishing’s Crypto Basics Series. We’ll be shipping all of our introductory web3 content on Mirror each Monday, enabling users to curate a web3 reference library by minting NFTs on Optimism.

Nothing Ventured

The history of organizations parallels the history of societies. Arguably, whenever humans come together in a structured social order with a particular purpose, it could be considered an organization. The latest evolution of organizations is emerging in the form of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) and it’s the type of organization we’ve been trying to create all along. A brief review of organizational studies highlights the direction organizations have been going and how DAOs can help us take the next leap forward. Much can be learned from each of the organizational theories described below, including their shortcomings, and how DAOs can incorporate wisdom from past developments into a new, truly decentralized theory of organizations.

While the origin of organizations stretches back into the history of kingdoms, regimes, and later governments, designing organizations for work is relatively new. Of course, even ancient civilizations had ways of organizing work projects, but these structures were quite simple. If a laborer wasn’t a slave who was forced to work by a cruel master, they were lucky to be paid some measly amount for their labor. It was mainly those who had no wealth or resources of their own, such as farmland, who had to work for others. Modern organizations have a much more complex system of power, incentives, and communication than the organizations that built the Pyramids of Giza or the Great Wall of China.

Sculpture of railroad workers. (Photo from Mike via Pexels)

Being More Thoughtful About Organizations: Scientific Management Theory

The last evolution of modern organizations began in 1911 with Fredrick Taylor’s book, The Principles of Scientific Management. Taylor argued that four activities needed to happen in order for organizations to run more efficiently and effectively:

-

Organizations extract and document all of the data about how each task in the organization is performed from the individual workers who best know each task.

-

Once the data are documented, organizations design more efficient processes, which need to be implemented in partnership with the workforce (i.e, not just ordered by decree of the management).

-

The organization implements a process of “scientific selection and progressive development” for its workers.

-

The work is then to be divided equally between management and the individuals performing the specific tasks to produce goods and services.

This became known as the “scientific management” organizational theory that led to the assembly line and a new baseline for modern organizations. There’s no doubt that developing a better understanding of specific processes that only exist in workers’ heads and documenting them in a scientific approach is beneficial (number one above). Most problems have arisen in activities #2 to #4. #3 has never really been done well by modern organizations and is the source of many issues but #2 and #4 are what concern us the most in trying to create better organizations.

Assembly lines of manufacturers circa 1940s (Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust via Unsplash)

In general, management is usually quite poor at including the frontline workers in the development and implementation of new processes, rules, etc. It is usually dictated to them and they are expected to comply. Even in Taylor’s day, he recognized the immense difficulty in achieving #4, which is still a problem today as most organizational leadership pushes the brunt of the work and real problem-solving to lower levels. Managers, especially in large organizations, tend to spend their time with (often unnecessary) meetings and paperwork, and making decisions with minimal real-time data and little or no involvement from the frontline workforce. Taylor thought management needed to be more actively involved in the production of work over a 100 years ago and it’s still a problem today.

DAOs have the innate ability to solve both of these problems as the members of the DAO collectively create new rules and processes as they go. There is no line between “management” and “workforce” when it comes to individual contributors, which allows for smoother and more sustainable implementation of organizational changes. Secondly, because an individual contributor can also take part in management, or governance, of the DAO, the work is inherently split evenly between workers and managers. In this respect, a DAO may actually have the ability to fully implement the scientific management model as Taylor had envisioned it.

Further Refinement of Organizations: Improving the Division of Labor and Calculating the Span of Control

A couple decades later, Luther Gulick (1937) expanded upon the principles of scientific management, specifically in relation to the division of labor. While the benefits of the division of labor were already long established by early economist Adam Smith, Gulick argued that how you divide up work tasks has a major impact on the outcome.

He postulated that 1,000 workers making shoes, each conducting every step from cutting leather to assembling the shoe parts might make 500 pairs a day. However, if you assigned those same 1,000 workers to only the tasks they were best at in the shoe-making process, they may work in an integrated way to create 1,000 pairs a day instead. This is because you eliminate inefficiencies that occur when someone is bad at a particular shoemaking task, slowing down the overall production (multiplied by all the other workers who are bad at other tasks in the process).

Another addition to organizational theory introduced by Gulick was that of “span of control” the idea that organizations need to be designed in a way that doesn’t require supervisors to have too many subordinates. Each organization is different and it also depends on the type of work being done but most organizations struggle with finding the balance here — how much control can a manager have on quality if they oversee 20 people? If you reduce the number of people one manager oversees, you’ll need more managers, which can be a drain on resources and could be more costly than it’s worth.

A manager organizing tasks and projects. (Photo by Jo Szczepanska via Unsplash)

The way we currently recruit for organizations now exacerbates both issues — project managers take educated guesses about who will be best for a particular job on their team — or worse, human resources chooses for them. We largely deal with the span of control through trial and error, if it’s dealt with at all. DAOs can solve these issues too. Members of a DAO choose their own tasks to do and the quality of their work is verified by multiple other members, not just a single manager. This negates the need for worrying about a manager’s span of control since there aren’t managers for specific people. In addition, DAOs accomplish work through individual tasks and projects rather than through jobs. This makes it much less likely for someone who’s not good at a particular task to continue doing it for long, even if they choose the wrong task to begin with.

Transformational Leadership: Another Top-Down Approach

Jumping forward in time a bit to the early 1970s, we see the concept of “transformational leadership” emerge as an organizational theory. The focus here shifted from how leaders can motivate and inspire all of the workers in an organization to personally identify with their work and a mission of the organization to drive success. While the idea is to develop many such leaders in a single organization, the examples given in the literature usually revolve around a single charismatic individual who single-handedly changes the course of an organization.

The problems with this approach are probably obvious — not only does it rely on a unique set of leadership skills that are very hard to train for, it is also a return to the dysfunctional top-down approach. When you have the unlikely event of Lee Iacoca coming along to turn around a failing car company or a Steve Jobs return and right the course of a wandering tech company, it works very well. Otherwise, the average organization is going to have trouble finding these types of leaders or trying to develop them internally.

The quintessential “transformational leader” addressing employees from a stage.(Photo by William Moreland on Unsplash)

DAOs don’t rely on transformational leaders. In fact, they don’t have organizational leaders at all. Instead, they use crypto tokens to administer voting rights. At a certain threshold of tokens, which for some DAOs is a single token, a given member may participate in making decisions about governance. This can be any member of the DAO, not just an arbitrary set of leaders. Leadership in DAOs happens in group form and this group has much lower barriers to entry than a traditional organization.

Getting to the Heart of It: Organizational Culture and Transparency

As it became clear that scientific management, carefully managing the division of labor and relying on transformational leaders wasn’t fixing the inefficiencies of organizations, the focus turned toward analyzing culture. Researchers like Steven Ott suggested that merely knowing the organizational processes and rules wasn’t enough to understand how they worked. It was the unwritten rules, customs, and informal practices that needed to be observed and accounted for when trying to decipher the organizational code. He suggests that “radical change” of an organization is only possible if you can uncover its culture practices and bring them to light in order to address them. An example would be after work gatherings at a local restaurant where decisions are sometimes made but only among those who attend these informal meetings.

Even when problems with organizational culture were identified, we still struggled to change them. Some of the largest tech companies like Google and Facebook have been aware of their lack of diversity for several years and have made little progress in changing their dominant white cultures. Despite Walmart’s efforts to convince us through TV commercials how much it values its workers, the Walmart corporate culture of treating employees as a liability is quite obviously here to stay.

A common modern brick-and-mortar workplace. (Photo by Proxyclick Visitor Management System on Unsplash)

The problem here is transparency. Even the most altruistic modern organization has a lot that happens behind closed doors. When it comes to DAOs, however, radical transparency comes with the territory. Every member of a DAO has the ability to take part in nearly any conversation, decision or process they wish, given that they have met the token ownership threshold. Of course, most wouldn’t be able to be part of everything that happens in a DAO but they don’t need to be since all of the transactions and decisions are recorded in the DAO’s blockchain.

The Flattened Hierarchy: a First Attempt at Decentralization

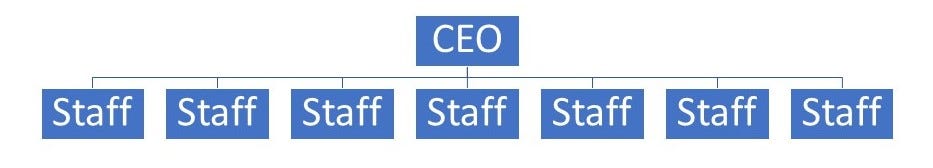

In the last 15–20 years, a number of organizations, such as IDEO, claim to have “flattened hierarchies” that have less of a top-down approach, decentralizing processes and decision-making. At least in theory. Julie Wulf of Harvard found that while these types of organizations claimed that they gave more decision-making power to lower levels than a traditional organization, their actual practices reflected the opposite. In these organizations, leaders such as CEOs had more direct reports than usual and less indirect ones (the “flattening” process depicted in Wulf’s writing). Because of this, senior leaders were closer to decision-making across the organization and thus had a hand in making decisions that would normally be made by someone lower in the hierarchy (and without any involvement from upper management). At IDEO, product design teams were purportedly autonomous, yet senior management inserted themselves to dictate how time was spent on the shopping cart project.

Going back to organizational culture, did these organizations with supposedly flattened hierarchies really think that changing the org chart would prevent those who have more political leverage and clout from having greater influence than others? It was a valuable experiment, but if the tools to manage the organization and methods of communication remain the same, the cult of personality will prevail.

A simple, flattened hierarchy.

DAOs are able to minimize outsized influence of individuals through (truly) decentralized decision-making as described earlier where the majority of the community is able to vote on most pivotal decisions. Everyone’s vote counts equally. A flattened hierarchy still has leaders such as CEOs and division managers. DAOs require no formal permanent leadership roles, allowing them to distribute power more evenly across its members to a degree that a flattened hierarchy in a traditional organization would not be able to.

Final Take: DAOs Are the Next Evolution of Organizations

The recent past of organizations, starting with scientific management up through flattened hierarchies, included important insights that all sought to help organizations become more efficient, more effective and even more human. DAOs signal the beginning of the next evolution, which will allow humans to collaborate in efficient, equitable and perhaps more effective ways than ever before. While they are currently confined to a small number of applications, their potential is great — especially in a time when millions of workers and businesses only recently realized their work can be conducted remotely.

As with any innovation, there is no shortage of challenges with DAOs to be overcome. One is the common practice of using governance tokens for voting, which can lead to inequalities when “whales” dominate token ownership and heavily influence voting. Another is the learning curve with the tools that are used for DAOs, like Discord and Collab.Land. DAOs need to spend a considerable amount of time onboarding new folks to these commonly used tools, not to mention the high digital literacy barrier that they create for many who could participate in DAOs (causing yet another equity issue).

Despite these issues, DAOs take a major step toward removing politics, concentrated power, exclusionary cultures and other inefficiencies from organizations, using technology to help us all be better at our work.

A version of this article was originally published by Bankless Publishing on January 21, 2022

Author Bio

Zero Mass is a writer exploring the unique space of DAOs and crypto. His pseudonym is purposefully designed to test the “trustless” concept.

Editor Bio

Hiro Kennelly is a writer, editor, and coordinator at BanklessDAO, an Associate at Bankless Consulting, and a DAOpunk.

BanklessDAO is an education and media engine dedicated to helping individuals achieve financial independence.

This post does not contain financial advice, only educational information. By reading this article, you agree and affirm the above, as well as that you are not being solicited to make a financial decision, and that you in no way are receiving any fiduciary projection, promise, or tacit inference of your ability to achieve financial gains.

Bankless Publishing is always accepting submissions for publication. We’d love to read your work, so please submit your article here!

Other Articles in the Crypto Basics Series

Decentralized Ledger Technology 101 by The Crypto Barista

The 101 on NFTs, A Briefing by Lanz

4 Simple Steps To Join a DAO by Samantha Marin

Towards Better Token Distribution by Paul Hoffman

Cryptocurrency Wallets 101 by ijeblowrider

How To Learn Solidity by oxzh

Ultimate NFT Red Flag Checklist by kalex1138.eth

Four Factors That Make a DAO Sticky by Peter Jones

14 Blockchain Basics by Hiro Kennelly

The Beginner’s Guide to Promoting NFTs by Monique Danao

DAO Governance Primer by EthHunter

The Three Pillars of Discord by Daryl, Lanz, and Roy

DEX Aggregator Basics by oxdog

A Beginner-Friendly Approach to Evaluating NFTs by Marc Bisbal Arias

7 Tips for Avoiding DAO Burnout by Frank America

The Importance of Self Custody by theconfusedcoin

DAI a Different Stablecoin by Jake and Stake

7 Etherscan Basics by Hiro Kennelly

DAOs Are Playgrounds for Growth and Development by siddhearta

How Web3 Writers Do Research by Samantha Marin