A Whirlwind Tour of Baseline Concepts for the Crypto Curious

Article by Hiro Kennelly | Edited by Trewkat and Tomahawk | Cover Art by pub-gmn.com

Welcome to Bankless Publishing’s Crypto Basics Series. We’ll be shipping all of our introductory web3 content on Mirror each Monday, enabling users to curate a web3 reference library by minting NFTs on Optimism.

Even if you’re brand new to crypto, you’ve probably heard of the Bitcoin and Ethereum networks. You may have even read about or interacted with Solana, Avalanche, Binance Smart Chain, Fantom, Cardano, or Algorand. On top of these better-known blockchains, there are hundreds (thousands?) of other blockchains in the cryptoverse.

The blockchain is the core technological advancement that enables our web3 world. The blockchains with the most activity share a number of core attributes. Among these attributes, the following 14 blockchain basics are key to understanding what makes the blockchain so revolutionary.

Blockchain Is Built Upon Distributed Ledger Technology

Distributed ledger technology (DLT) underpins all we do in crypto. At its simplest, DLT is a connected group of computers in different locations that use various rules to maintain a canonical, synchronous copy of validated transaction data across the network. Through these rules, called a consensus mechanism, data is added to the shared ledger. A blockchain takes DLT one step further by cryptographically recording data chronologically into blocks that are then ‘chained’ together through this chronology. Hence the term blockchain. A blockchain is essentially a cryptographically secured distributed and decentralized database of chronologically listed transactions.

Blockchains Are Also:

Geographically Distributed

It’s easy to conflate the terms ‘distributed’ and ‘decentralized’, but blockchains are both. Distributed refers to the idea that the validators who make up the blockchain network are located in geographically diverse regions — that is, the connected computers running a synchronous copy of blockchain data, the ‘nodes’, are in different physical locations all around the world. Distribution is a vital feature; you can have one million computers running a copy of blockchain data, but if they are all in the same zip code and that area gets hit by a natural disaster, the blockchain goes offline.

Decentralized

Decentralization of a network’s validator nodes is necessary to ensure that no single faction can control the blockchain, compromising its security. All blockchain networks exist on a spectrum of decentralization, meaning that some blockchains are more decentralized than others. Since all of the nodes that make up the blockchain network each have a synchronous copy of the state of the system, no single node or entity is in charge or responsible for the full network. This is a highly fault-tolerant design.

Transparent

One of the key features of blockchains is that the information recorded on them is transparent, meaning it’s available for all to see. While we can all access public blockchain data through front ends such as Etherscan, even private blockchains give full viewing rights to anyone who is granted access to the chain. The transparent nature of the blockchain is highly useful, both for simple features like users tracking their transaction history and also for more complex analytics such as those used to catch cybercriminals.

Immutable and Secure

Powered by cryptographic hashing (essentially an algorithm that enables a secure digital signature), immutability means that once data is recorded on chain, it cannot be changed or modified. In this way, the blockchain is also censorship resistant. Once the information is on chain, it’s virtually impossible to remove.

The immutability of the blockchain means transactions are secure, but the cost of this permanence can be measured by the issuance rate of its native token — the reward paid to validators to process transactions by proposing and validating new blocks into the blockchain. In theory, this secures a finite amount of transactional value, a ‘security budget’ if you will, which directly scales with the price of the native asset that is being issued. For example if the price of bitcoin doubles, all else being equal the dollar value that the Bitcoin network secures will double as well. The more decentralized the network and the more nodes it has, the more secure the blockchain can potentially be, due to improved resiliency to an attack.

Trustless

Enabled by the immutable nature of the blockchain, ‘trustless’ refers to the fact that you don’t need an intermediary or trusted third party to broker transactions or to keep your assets secure. In decentralized finance, the user can interact with smart-contract code for their financial services and eliminate the need for a custodian of funds. The trustless nature of the blockchain also ensures that peer-to-peer transactions, which underpin much of what happens in web3, are seamless. Having custody of your own private keys is crucial to making this work, as the holder is always the one who must be trusted to safeguard funds (an idea embodied in the phrase ‘not your keys, not your crypto’).

Permissionless

The public blockchains that we interact with in web3 shouldn’t, in principle, require anyone’s permission to use, meaning there is no network administrator to keep you from participating (or to help you when you experience an issue). Decentralized applications are simply open and ready for your wallet connection, and you can authorize interactions if the funds are available. With a permissionless blockchain, anyone is free to read and write to the blockchain, participate in the block creation consensus mechanism, or further build within the ecosystem.

These first seven characteristics go to the nature of blockchains, the overarching goals that systems are designed to achieve, and why the technology is so revolutionary.

The following seven build on the above, and while not more advanced concepts per se, they do require a bit more understanding.

Degree of Decentralization

While distribution is important for network robustness, decentralization is the metric to which most crypto natives pay attention. The more nodes running copies of the data, the more decentralized the blockchain. A more decentralized blockchain is a more secure blockchain.

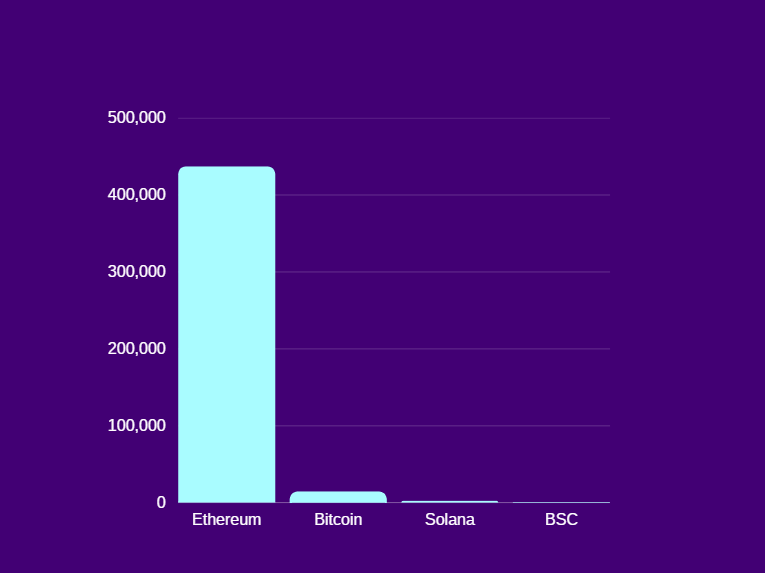

As the above graph illustrates, not all blockchains are created equal. BSC is basically a centralized blockchain, while Solana is relatively better. Bitcoin is about seven times more decentralized than Solana, and post-Merge Ethereum became more decentralized than Bitcoin by a factor of 30. There are currently over 430,000 validators on Ethereum’s proof-of-stake network.

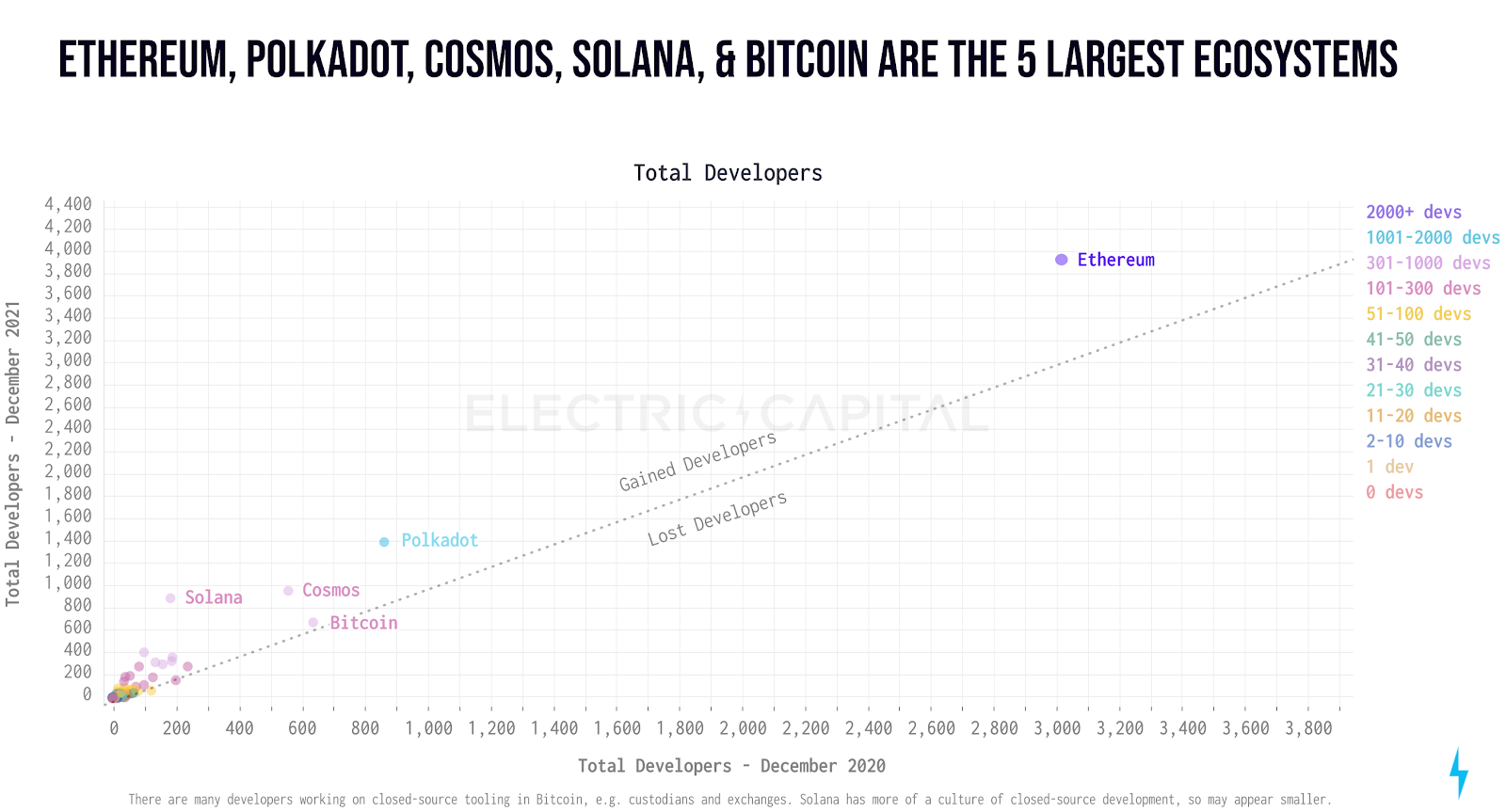

Follow the Developers

A key indicator to pay attention to when considering where to deploy capital on chain is the number of developers actively building within the ecosystem. The more developers active within the ecosystem, the more projects being built. The more projects being built, the more users within the ecosystem. The more users, the more devs… and the cycle continues. As the below chart indicates, the Ethereum ecosystem far and away has the biggest draw for developers.

Consensus Mechanisms

A consensus mechanism is the method by which network validators — those who arrange transactions, build blocks, and keep the synchronous data — reach agreement on what data to include on chain. A functioning consensus mechanism assures that all network validators have the same data on their computers.

The first consensus mechanism was Bitcoin’s proof-of-work, which relies on validators using high amounts of computing power to solve complex algorithms known as hash functions. Each block on the chain has a specific hash function, and the first miner to solve that function (which is sort of like finding a random number in a huge dataset) gets to create the block and is rewarded in bitcoin. The other network validators can run the hash function to check the work, and in this way the integrity of the data on the blockchain is preserved. Many major blockchains currently use proof-of-work, although that is starting to change. Ethereum recently transitioned to a new consensus mechanism called proof-of-stake.

It’s estimated that proof-of-stake is 99% more energy efficient than proof-of-work. With proof-of-stake, network validators stake the blockchain’s native currency to secure the network. This capital, this stake, can be reduced or eliminated — called slashing — if the validator behaves dishonestly or lazily. Dishonesty means the validator is attempting to include fraudulent transactions, while laziness means that the validator doesn’t propose blocks or their node experiences excessive downtime.

Although there are dozens of other consensus mechanisms, proof-of-work and proof-of-stake are by far the most common.

Native Tokens

All blockchains have a native token that allows you to pay for transactions within the network. For Bitcoin, it’s bitcoin (BTC); for Ethereum it’s ether (ETH); for Solana it’s SOL; for Avalanche it’s AVAX, for Polkadot it’s DOT, and for Cardano it is ADA. While these native tokens serve as the blockchain’s currency, they are also distinct tradable assets, listed on various centralized and decentralized exchanges. Each of the various tokens also carries with it a strong supporter base and certain narratives around its qualities and value. Bitcoin is referred to as a store of value; it’s also known as digital gold, whereas ether is often referred to as programmable magic internet money or ultra sound money. But the main takeaway is that the native currency is used for transactions but can also have secondary characteristics.

Bridges

A bridge is the name for a protocol that enables users to move cryptocurrencies between various blockchain networks. Bridges let users move assets or data to unrelated ecosystems, such as bridging ether to the Solana network; or within the Ethereum ecosystem, to Layer 2 scaling solutions and side chains. Notably, when using a non-native token of another blockchain, that token will be wrapped. This is essentially a synthetic version that tracks the native token. Examples include wBTC, which allows the use of bitcoin on Ethereum, or wETH, which allows the use of ether on other blockchains. Bridges also allow users to connect to dApps (decentralized applications) within other ecosystems. Bridges can be centralized or decentralized, and rely on liquidity to move assets back and forth. Pro tip: it’s good practice to check a bridge’s liquidity before transferring assets, and you generally only want to bridge native tokens.

Forks

A fork, in blockchain terms, is a change to the protocol. Forks are typically used by blockchain developers to upgrade the blockchain, although they have also been used to roll back the blockchain. There are two types of blockchain forks: hard and soft forks.

A hard fork is a backward-incompatible upgrade, meaning that nodes on the old blockchain cannot validate blocks on the new chain and similarly the new chain cannot validate blocks on the old chain. Sometimes hard forks happen because of community disagreement, as with Bitcoin Cash, which came to fruition because of scaling disagreements within the Bitcoin community. Ethereum was hard forked after The DAO Hack, and Ethereum Classic was created.

Unlike a hard fork, a soft fork is forward-compatible, meaning the split blockchains can still interact after the fork. With a hard fork, all validators need to agree to the change or a split occurs, as discussed above. With a soft fork, only a majority of validators need to agree on the change.

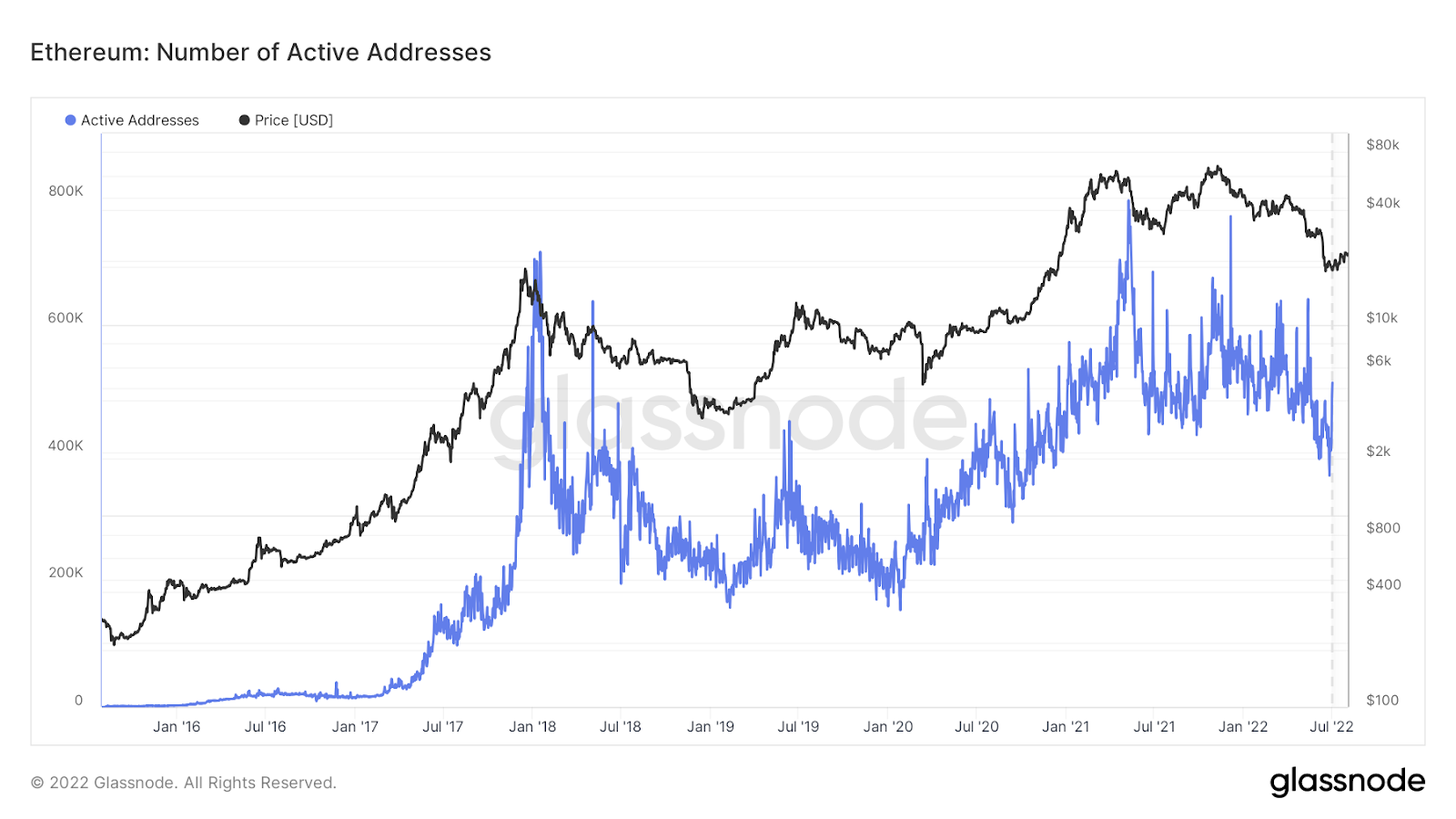

Active Addresses

The number of active wallet addresses on a blockchain is another great way to determine the amount of network activity. An active address is defined as a unique address that either sent or received a cryptoasset within a defined period of time. It should not come a surprise that the number of active addresses rises and falls with the overall crypto market.

Blockchain Basics Are Sometimes Not So Basic

Depending on your experience to date, some of the more complex blockchain concepts such as consensus mechanisms, forks, and bridges may not seem that basic. This is where we have to expand our minds as to what is basic. Living and working at the cutting edge of the technological world means that there is a lot of information to absorb. While not all of this material is simple, it’s still basic in that it is absolutely essential to understand these principles in order to confidently navigate this emerging system.

Take the time to learn these baseline concepts now so that when you encounter these terms or you are ready to dive deeper, you’ll have a foundation upon which to increase your learning. Like the blockchain, our web3 education is really a series of building blocks on which we stack and link our knowledge. As with all things web3, together, we go further.

A version of this article was originally published by Bankless Publishing on September 29, 2022.

Author Bio:

Hiro Kennelly is a writer, editor, and coordinator at BanklessDAO, an Associate at Bankless Consulting, and is helping to build a grants-focused organization at DAOpunks.

Editor Bios:

Trewkat is a writer and editor at BanklessDAO. She’s interested in learning about crypto and NFTs, with a particular focus on how best to communicate this newfound knowledge to others.

Tomahawk has been writing and editing at BanklessDAO from inception, and entered the crypto space as an investor in 2017. He’s a big believer in the power of tokenized mission-aligned communities and the massive potential Ethereum offers to solve humanity’s most pressing coordination failures.

Designer Bio

Pub-gmn.eth is a blockend developer.

BanklessDAO is an education and media engine dedicated to helping individuals achieve financial independence.

Bankless Publishing is always accepting submissions for publication. We’d love to read your work, so please submit your article here!

This post does not contain financial advice, only educational information. By reading this article, you agree and affirm the above, as well as that you are not being solicited to make a financial decision, and that you in no way are receiving any fiduciary projection, promise, or tacit inference of your ability to achieve financial gains.

Other Articles in the Crypto Basics Series

Decentralized Ledger Technology 101 by The Crypto Barista

The 101 on NFTs, A Briefing by Lanz

4 Simple Steps To Join a DAO by Samantha Marin

Towards Better Token Distribution by Paul Hoffman

Cryptocurrency Wallets 101 by ijeblowrider

How To Learn Solidity by oxzh

Ultimate NFT Red Flag Checklist by kalex1138.eth

Four Factors That Make a DAO Sticky by Peter Jones