Lockdrop + Liquidity Bootstrap Auction Emphasizes Price Stability and Community

Article by Paul Hoffman | Edited by Hiro Kennelly | Cover by Cosmic Clancy

Welcome to Bankless Publishing’s Crypto Basics Series. We’ll be shipping all of our introductory web3 content on Mirror each Monday, enabling users to curate a web3 reference library by minting NFTs on Optimism.

A Primer on Tokenization

With the introduction of a novel blockchain protocol, decentralized application, or DAO (collectively, “protocol”), one of the primary questions to be answered is, “How should the native token be distributed?” It’s not a very complicated question, but finding the right answer that takes all the variables into account is critical.

There are a number of goals a fair token launch should achieve. First, there are legal frameworks to consider. Any serious protocol should adhere to legal requirements in an effort to safeguard themselves and the token recipients.

Initial coin offerings (ICOs), for example, have fallen out of favor as a distribution model because the U.S. legal framework deems ICOs a security and therefore only available to U.S. accredited investors. This distribution method would therefore be unavailable to a significant portion of crypto-economic participants. Instead, it’s desirable to have as many users as possible be able to participate in a fair distribution of tokens.

Second, the token should be distributed to the “right people.” Here, the right people are the users who are engaged and are generally aligned with the best interests of the protocol. They are the type of people who will support the community long term, actively participate, and contribute value to the ecosystem. The distribution should also try to exclude token launch manipulators such as whales (people who hold inordinate amounts of a single token and can manipulate the market by sheer weight) or bots that use their wealth or speed to exploit token distribution models.

The third element of a successful token launch is a price discovery process that doesn’t severely damage the portfolios of the people holding it. This requires sufficient liquidity (amount of tokens at a particular price) and float (defined here as the percentage of the total token supply that’s available) that can absorb market supply and demand virtually from day one.

The benefit to sufficient liquidity and float is quite straightforward. When a new token gets released to the wider crypto-economic system through a (decentralized) exchange listing, price discovery can be quite volatile and can potentially be manipulated by wealthy actors. When liquidity and available float are low, large token holders have the power to inflate or deflate the value of the token quite substantially.

Although volatility can be spectacular and interesting, it is not very desirable for the longevity of a protocol, simply because a lot of people can get hurt in this phase of price discovery, and you may hurt exactly those users who would otherwise be long-term stakeholders.

Consider the situation of high demand but low supply. Suppose the market is ready to buy 10% of the token supply, but float is only 1%. The price of the token would initially skyrocket as demand far outstrips supply. This mania phase may be very exciting for holders of the tokens, but because 99% of the tokens still have yet to come to market, this value is purely based on the supply constraint and is impossible to sustain. As a result, the long-term outlook on the token price isn’t too good.

Take for example Yearn Finance. Following criticisms that Yearn’s operations were too centralized, founder Andre Cronje quickly spun up the YFI governance token with a total supply of 30,000 tokens and airdropped it to prior users of the protocol. Andre was quick to point out that these tokens were worthless, would not be listed on exchanges, and would only allow owners to participate in Yearn’s decentralized governance. The market, however, did not share his assessment of the value.

This was during the 2020 “DeFi summer” when many protocols were seeing their native governance tokens producing explosive returns, and the market was insatiably hungry for YFI, this ultra-low supply DeFi token created by one of the most famous developers in the space. It was the perfect recipe for a moon shot. The liquidity was low, since the protocol didn’t participate in market making. It was initially just those users who wanted to cash in on their airdrop who provided their own liquidity on automated market makers (AMMs). There was very high demand and several large exchanges listed YFI right after the airdrop, which allowed thousands of investors to buy the token in a short time.

So we see that the result of a high demand, low supply scenario is a massive run up followed by a long, slow bleeding of the market price. This hurts people who buy into the hype and demotivates community members who want to hold the token. In addition, those who obtained tokens early on will be highly motivated to sell during the initial mania phase, and may not even participate further. Neither of these aspects are desirable for the long-term prospects of a project.

Conversely, a setting in which the demand is low and the supply high will achieve a similar outcome (downward price momentum) but without the initial upward spike. This is because with ample supply and little demand the price can essentially only trend negative.

In layman’s terms, what you want to do as a protocol is release an appropriate amount of the token to as many core community members as possible, at an already “discovered” price (near fair market value).

From thereon, you want the merits of the protocol to determine the price discovery over time.

Token Distribution Models

Let’s jump into a few quick examples of token distribution models and analyze their pros and cons.

Venture Capital

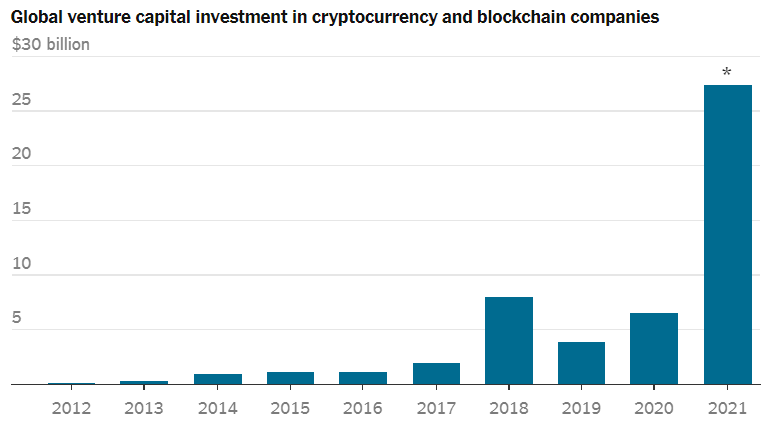

Consider the venture capital (VC) route. Many protocols, simply due to their upfront costs of producing, go through series A, B, and even C rounds of funding before they go live (check out this cool source for VC funding). The Solana blockchain project is an excellent example of this.

The upside to the VC route is that Solana’s developers had access to capital from day one, but equally important is that VCs tend to have a pretty good network of experts, technicians, and developers to help build products and provide feedback. With the help of VC money and a network of accessible talent, Solana’s developers could take this project from idea to launch in relative quickly, focusing on the protocol instead of community building.

The downside to this is fairly obvious. VCs expect sizable token stakes for their investment. And given the fact that VCs are taking a massive risk investing in an idea (Solana wasn’t anything more than a whitepaper during the initial raise), they want the potential for massive upside, too.

That being said, some of the initial rounds for Solana went for 4 cents per SOL, in which over 16% of the initial tokens were sold. The next batch went for 20 cents (13%) and the batch after that 22.5 cents (5%). In other words, one third of the Solana tokens in existence were sold for between 4 and 22.5 cents. This resulted in massive returns for the VCs that participated.

Now, I don’t have a problem with people getting rich. The point is that aggressive early seed investing can make a protocol whale-heavy. Unlike those who buy because they believe in the project, these whales got in early at a sizable discount and therefore are capable of selling at any price.

For VCs, no matter how dedicated or convicted, those 1000x bags will feel very heavy. In fact Solana has the largest “insider” token allocation of any popular blockchain. That’s a lot of heavy bags.

Then comes along an average user like you or me who generally buys in at a higher price and will get dumped on by VCs who are up 1000x. The effect is not good. People get hurt and become sellers at a loss. They are then less likely to use the platform, less likely to build on it, and by extension, less likely to help build a community of shared values.

A little bit of context here: by no means are all VCs or angel investors greedy whales or bag-heavy market sellers. Otherwise, crypto would simply be a land-of-losses wherein only a select few walk away with the profits. The point I’m trying to make is that in the most desirable scenario, from the perspective of protocol longevity, having tokens in the hands of users that have the protocol’s best interest at heart is the most desirable.

The VC method essentially has a difficult time getting the tokens to the right owners without depreciating value. However, the VC method is generally a good way to get started but a difficult train to keep going, and investors generally don’t like it (for good reasons).

The Airdrop

Let’s look at another token distribution model, the token airdrop. Popularized by UNI in 2020 and more recently, ENS, SOS, and LOOKS, each early user or ecosystem participant is given an allotment of free tokens based on their ownership, participation, or similar metric. In theory this is great, since early users can try something and get rewarded for it.

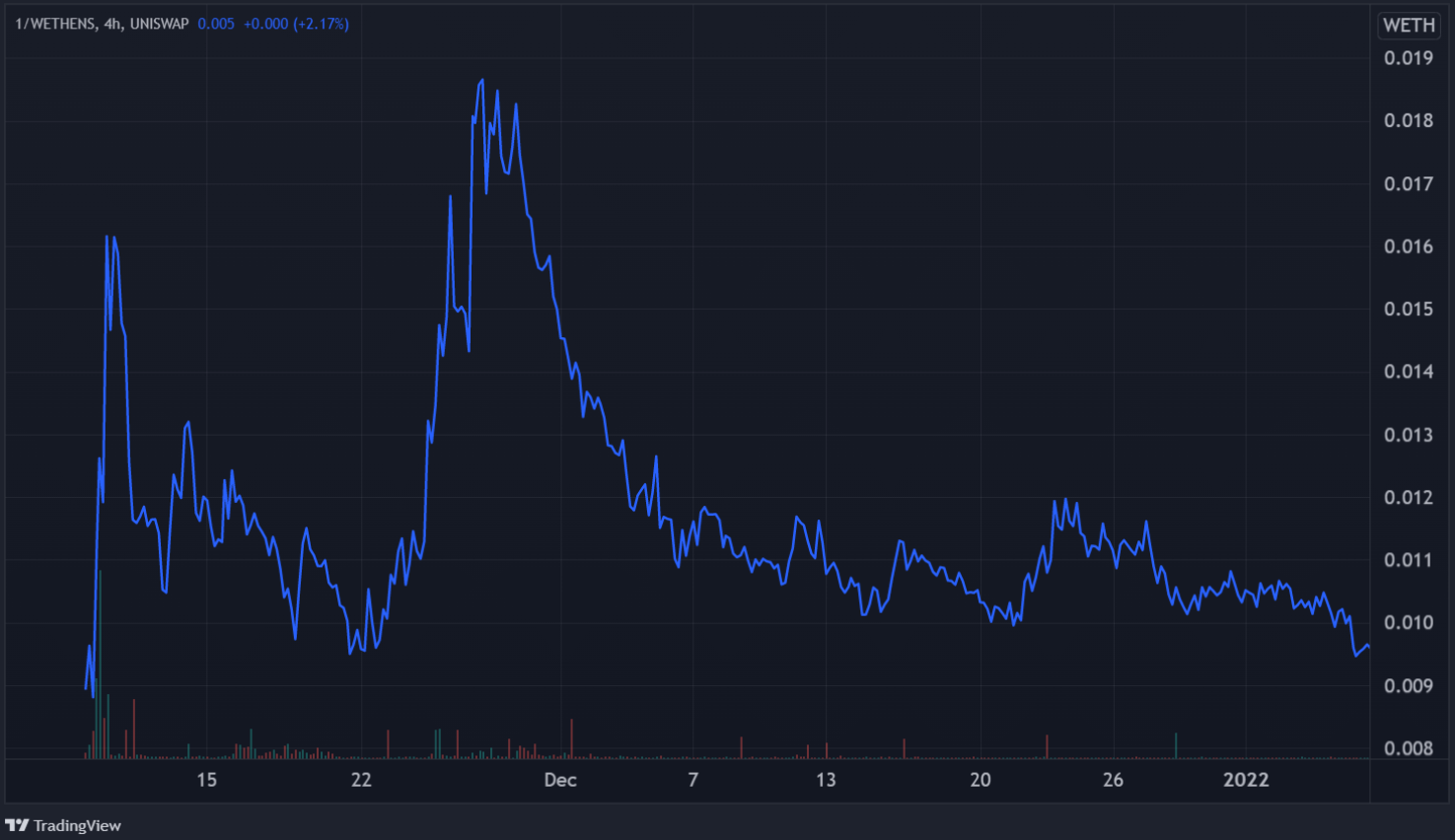

But there are a couple of problems here too. First of all, a lot of the airdrops come out of nowhere, and price discovery can be extremely volatile. ENS is a good example of that:

Often, airdrops are unannounced so there is no front-running, and as a result, there is little time for communities to organize. These new stakeholders are expected to figure it out and start governing right away. This creates a lot of fervent energy following the token drop, but as the difficulties of governance come to light and the initial novel energy dies down, the zeal behind the project can quickly peter out.

Although token airdrops generally come with a lot of volatility and are difficult for the community to organize around, they do come with some interesting wins. For example, it’s pretty easy to engineer a large and widely distributed float, and it’s also easy to reward the right users through their wallet interactions. After all, the blockchain stores an immutable record of these transactions. If you, as a power user, have frequently used a particular protocol in the past, it’s easy to be identified and rewarded appropriately.

A potential drawback of the airdrop model is a lack of funding mechanisms for early development. Since the tokens are minted out of thin air and given away rather than sold, the developers need a separate source of funding to get the project off the ground. Often this is done via retrospective token allocation to the development team, meaning that all the work up until the airdrop is done via sweat equity (unfunded labor that will be repaid later when the protocol is up and running). Depending on the scale or complexity of the protocol, this may not be a practical way to launch.

Both the venture capital and airdrop token distribution models have their pros and cons. Venture capital helps during the launch phase of a project, but oftentimes has a skewed token distribution. Airdrops, on the other hand, are easier to balance in terms of token distribution but have unpredictable pricing volatility and are difficult to organize around.

A New Contender in Token Distribution

Enter the lockdrop + liquidity bootstrap auction, or LLBA for short. The LLBA is being touted as an innovative token launch strategy developed by the folks at Delphi Digital. Delphi is a well-respected research institute, and it would serve to pay attention to early projects that use the model. If this distribution method is deemed successful, it will be implemented by other blockchain projects.

In what follows, I’ll provide a detailed look at Delphi’s LLBA distribution model, how it works in theory, what its practical implementations are, how it compares to other models, and its advantages and drawbacks.

Lockdrop + Liquidity Bootstrap Auction (LLBA)

The lockdrop + liquidity bootstrap auction (LLBA) works in three distinct phases. The first phase is the lockdrop phase, also known as the distribution phase. In this phase the tokens are distributed to the protocol’s stakeholders, but they are unable to be immediately claimed.

Phase two is a liquidity bootstrap auction, this is where price discovery happens and liquidity is established. Here, token recipients can commit their tokens to a liquidity pool consisting of the launching token and a stablecoin. Phase two is actually a two-stage auction phase for market-based price discovery. This mechanism is critical to mitigate risk, and we will spend more time describing this in detail a bit later.

Finally, phase three is when the airdrop is unlocked and the token begins trading publicly.

In summary:

-

Phase one: distribution

-

Phase two: auction (consists of two parts)

-

Part 1: all token and/or stablecoin deposits accepted, stablecoin withdrawals only.

-

Part 2: no further deposits accepted, available stablecoin withdrawals limited and throttled down to 0% by the end of the auction.

-

Phase three: public trading

Phase 1: Distribution

Let’s consider a hypothetical protocol with native token ‘TOKEN.’ Remember, phase one distributes TOKENs to the users and stakeholders of a protocol. Here it is desirable to distribute the tokens to the users that bring the most value to the protocol. How this value is measured is completely at the behest of the protocol.

For the recently launched Astroport, the tokens were distributed to those who provided liquidity in key trading pairs. For Altered State Machine, the tokens will be distributed to those who hold the genesis NFTs (ASM brains and AIFA all-stars).

An airdrop distribution method is also regulatory-friendly, as it does not require a protocol to sell tokens to fund operations (the ICO model). The LLBA distribution phase is similar to an airdrop in the sense that users get rewarded for past actions, perhaps by using a protocol, owning an NFT, or providing a service. This is what I consider a backward-facing airdrop. In other words, this airdrop rewards users for past actions which provided value to the protocol or ecosystem.

An interesting twist with the LLBA distribution model, however, is that it also contains a forward-facing airdrop, in the sense that it will reward users with forward-facing commitments to use the protocol.

What’s a practical example? Users who agree to lock up their tokens for a longer time period might get a larger share of the distribution. This method has similarities to the way Yearn Finance and ve(3,3) increases the rewards for users who lock up their respective tokens for a longer time, with the difference being that it’s applied to an airdrop as opposed to a staking program.

LLBA phase one distribution essentially works similar to a regular airdrop, with the extra feature that those who make a forward-facing commitment get rewarded for it. What this achieves is rewarding the right users, those who are committing to long-term use of the protocol, advantageously.

In addition, users making forward-facing commitments have an incentive to contribute to the protocol and the community during the early phases of a protocol to help ensure its success.

Phase 2: Auction

The second phase is the liquidity bootstrap auction. The core functionality of this phase is for price discovery, and secondly, creating deep liquidity at the discovered price.

The way this works is as follows: users who have received the token in the distribution phase have the choice of depositing some or all of their token allocation into a liquidity pool. Typically, this is a token-stablecoin pair, but other liquidity pairs could be considered. Let’s say for this example that TOKEN pairs with stablecoin DAI for its liquidity.

The effect of adding TOKEN to the liquidity pool is increasing its supply relative to the DAI deposited, which lowers the price. On the other side of the equation, market participants who missed out on the airdrop (or anyone who wishes to buy more tokens) may add DAI liquidity to the trading pair and gain exposure to TOKEN before market listing; this raises the inferred price of TOKEN and creates demand. During the auction phase, an equilibrium between supply and demand will naturally form, and a fair price is established.

As more tokens and/or stablecoins get added to the liquidity pool, the TOKEN-DAI ratio adjusts to reflect the new reality. In simple terms, if more tokens get added (increased supply), the price drops. If more stablecoins are added to the liquidity pool, the price increases (increased demand).

In our simplified example: if the auction has gathered 100 TOKENs and $100 in DAI in the liquidity pool, the price for 1 TOKEN is $1. If another 100 TOKENs are added to the pool, thereby increasing the total number of TOKENs to 200, the price would be $0.50 each. Conversely, if there are 100 tokens and $200 DAI in the pool, the price per TOKEN is $2.

In addition, and crucially, the auction phase effectively has two parts. In part A, anyone is allowed to deposit as many tokens and stablecoins as they want, however it’s only possible to withdraw stablecoins.

I’ve reached out to the team at Delphi to explain why individuals can only withdraw stablecoins. The simple reasoning behind it is that it makes the pricing mechanism less complex and thus, easier to work with and predict for users.

In part B of the auction phase, the percentage of stablecoin liquidity that one can withdraw from the pool is throttled over time, slowly locking this liquidity into the pool.

For example, early on in the throttling phase you may be able to withdraw up to 50% of your DAI. A bit later the throttle is at 65%, so then you’d only be able to withdraw 35% of your DAI. On the final day, the final hour, throttling might be at 99%, and you can only withdraw 1% of your stablecoin deposit.

In addition to this throttling mechanism, only one withdrawal can be made throughout this period. This is obviously to stop users from withdrawing 50%, then 50% of 50%, and so on, thereby gaming the system.

Here is a practical example of the two part phase 2 auction as implemented by Astroport:

This is a little complex to wrap your head around at first, I know.

The goal here is to have price discovery happen in a reasonably predictable way that is extremely difficult to game. You may be wondering, “Why all the throttling and only being able to withdraw once? That sounds hella scammy!” Well, actually the opposite is true.

The throttling and single withdrawal is to make sure that whales cannot game the token price discovery by dumping tokens into the pool or pulling out all their stablecoins at the last minute. I’ll touch more on this issue in the critical analysis subsection.

For now, just understand that what the auction phase achieves is market price without the price discovery volatility, it gives users who missed the initial distribution an opportunity to purchase at a market-denominated fair price and inhibits market manipulators from gaming the distribution model.

Equally important, because users are trading with other users rather than the protocol selling to users, it is not an illegal securities sale from a U.S. regulatory perspective.

Another important note is the fact that participating in phase 2 requires users to commit their tokens to a liquidity pool, which might expose users to impermanent loss. Thus users typically need an incentive.

Liquidity providers can be incentivized in a number of ways, but in general the fairest method is a predetermined number of tokens (which could be 1–2% of the total supply) shared among the liquidity providers. The benefit to this implementation is that it’s easy to implement, rewards users proportionally to the risk they take (fewer liquidity providers = higher rewards), and as far as I can see, has no long-term downsides.

Other incentivization mechanisms could be considered however. Ultimately this is at the behest of the protocol.

Phase 3: Open Trading

This part is straightforward; phase 3 opens the liquidity pool and the participants to the wider crypto-economic system. Historically for significant protocols, this milestone sparks a flurry of trading activity and can result in volatile price behavior. The LLBA model should temper this somewhat, since token holders are incentivized to lock up their airdrop rewards, and the auction phase allows for an early price discovery mechanism. This makes the market release of the token much less speculative, less volatile, and easier to enter or exit.

Let the trading commence!

Critical Analysis

The lockdrop and liquidity bootstrap auction (LLBA) is novel and comes with considerable advantages over other token distribution models.

In short, LLBA aims for a fair distribution that favors long term stakeholders, a price discovery process that minimizes volatility, and sufficient liquidity to facilitate growth and adoption. It’s also fully compliant with all major regulatory frameworks.

Arguably, decentralization of the token holders is considered an advantage of LLBA because there’s such a large float. “The potential influence of pre-launch builders on post-launch token-based governance is diluted, making governance decentralized much earlier than usual,” wrote Jose Maria Macedo.

However, achieving a flat distribution, in the sense of all drop participants receiving an equal share, is not a core feature of the LLBA. Put simply, wealthy market participants are not inhibited from buying a larger share of the available tokens during and prior to the distribution phase and can thus still have an outsized role to play in the tokenomics and the future of a protocol. A wide and flat distribution is something contemporary NFT launches can accomplish much easier.

This does not discredit the distribution method in any way, because the goal is not to stop whales from using their wealth to participate in the token launch; it is to stop whales from gaming the token distribution. This is reinforced by refusing token deposits after a certain time and by throttling the removal of all stablecoins at the end of the auction phase.

To be precise: without this two-part feature of the auction phase, a market manipulator could add a large stablecoin position to the pool during the early auction phase, pumping the implied token price. The effect hereof is that the token becomes considered overvalued (demand outstrips supply). In turn, the overvalue entices more token holders to deposit tokens to the liquidity pool and deters other stablecoin depositors from participating. This effectively creates a scenario wherein the market manipulators are the largest majority of the token buyers because they’ve outpriced the competition at an early stage.

The next move is for the market manipulator to remove a large share of their stablecoin just before the auction phase is over, thereby crushing the value of the token (lower demand = lower price) without sufficient time for auction participants to remove tokens from the pool or recognize the new pricing reality and add stablecoins to the pool. Another result of this scenario is that it can grant the market manipulators a large share of these same tokens at a greatly reduced price once open trading commences.

What the LLBA model successfully does is inhibit this manipulation game by ending token deposits and throttling the removal of stablecoins during the second part of the auction phase. This theoretically stops manipulators from creating last-minute volatility in the token price and therefore a step in the right direction in terms of establishing a fair price discovery mechanism where all participants have ample time to react.

Potential Downsides

The LLBA model does place a lot of trust in the development team because users cannot access their tokens as part of a lockup. Contrary to an airdrop distribution that distributes all the tokens from day one, the LLBA model requires users to trust the team to not pull the rug during the time their token is locked.

This capital inefficiency and the inability to react to protocol developments, market conditions in the wider crypto-economic space, or other news is one of the major downsides to having tokens locked up — this is a risk that early investors will have to weigh when determining their lockup time.

Another element to consider with extended lockups is the fact that OTC secondary markets pop up where locked positions can be traded at reduced costs. This has notable implications for price discovery.

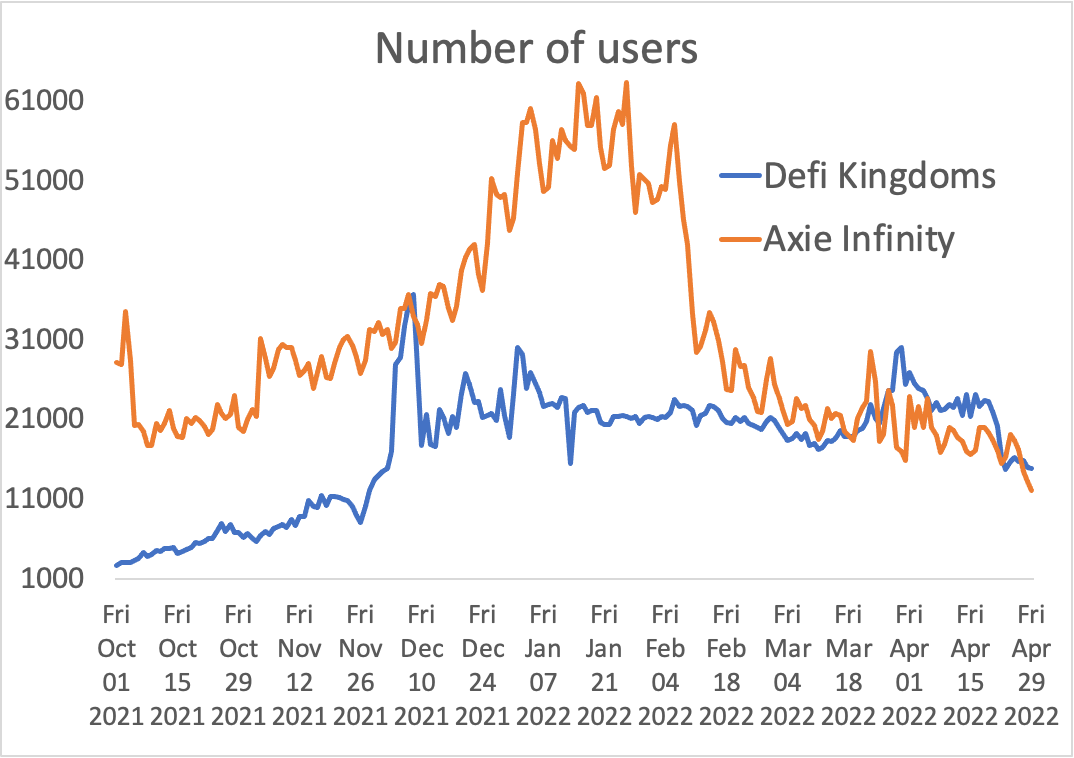

In order to demonstrate how this materializes, I’ll take an example from recent developments in DeFi Kingdoms (DFK). In DFK, users are incentivized to stake. Once they stake, newly minted tokens are unlocked over time (1 year max). What users have figured out is that you can trade these locked positions over-the-counter, notably at a high discount to the nominal value.

The effect is tangible; as more and more users realized this deep discount, they began selling the unlocked tokens to acquire more locked tokens, and the price of the unlocked tokens suffered immensely. For those looking to get into long-term positions, it was simply much cheaper to buy locked vs unlocked tokens (for example, $2 per JEWEL token locked for 10 months, versus unlocked JEWEL at $17, although given it was over-the-counter trading, I have no secondary evidence for this other than hearsay). Consequently, the DFK developers have proposed and passed a change to the smart contract that put a halt to this OTC trading behavior.

What this example demonstrates is that tradeable locked positions can be to the detriment of lockdrop and auction participants. It therefore serves to keep an eye out for tradeable locked positions and consider carefully whether participating in the lockdrop and/or auction is worth this risk.

Essentially, the trading of token derivatives such as these locked tokens creates an unintended price discovery vector. In another example, Altered State Machine (ASM) will launch using an LLBA, however the NFTs that grant users a fair share of the drop will trade openly on the market. This undermines some of the important work the LLBA does in terms of price discovery and inhibiting volatility.

Arguably, this example is not the strongest point of contention in the LLBA model, simply due to the fact that the ASM NFTs offer additional utility on top of being required for the airdrop, and in this case, price discovery hasn’t been seriously volatile. Also, for savvy investors, this mechanism can provide an advantageous entry point if the protocol is successful.

What should be noted, however, is that when the LLBA model is considered, or investigated from an investor’s perspective, the mechanism that determines who receives what size of token allocation should be critically analyzed. In addition, any project launching with an LLBA by making use of an NFT or token (without additional utility) should be seriously questioned, as this could undermine the legitimacy of the LLBA model.

LLBA a Step in the Right Direction

Token distribution is very difficult to get right. Allocating tokens to the right people, avoiding regulatory pitfalls, and making sure that the model cannot be gamed can be a herculean task.

The LLBA aims to achieve this goal by adding a forward-facing incentive to the airdrop by locking tokens for extra reward, hence the term ‘lockdrop.’ In turn, token holders can place these tokens in a liquidity pool where price discovery happens in a non-volatile, non-corruptible manner that aims at providing adequate liquidity from the moment LLBA enters phase 3, open trading.

Some elements of critique, however, are warranted. For example, the LLBA model is not all-encompassing, meaning that price discovery prior to LLBA can be volatile if the distribution of the tokens is based on an NFT or secondary token without utility. As the DeFi Kingdoms example demonstrates, the current value of a token can be significantly influenced by OTC trading that offers large discounts on locked tokens (similar to a futures market in backwardation). This undermines the lockup process and fair price discovery by extension, thereby negating much of the benefits the LLBA initially provides.

The LLBA, complex as it is, ultimately appears to be a big step in the right direction. It provides a framework wherein volatility is limited, yet price discovery happens naturally. The initial float is substantial, tokens generally go to the right users, and crucially, it doesn’t run afoul of U.S. securities laws.

It’s going to be very exciting to see how protocols will iterate the LLBA model to achieve successful token launches. Examining where or how the coming implementations of the model eventually fail and the ways they are improved upon will be equally interesting. Once some new case studies have provided additional insight on the art of token distribution, it’ll be time for a follow up analysis.

A version of this article was originally published by Bankless Publishing on May 06, 2022.

Author Bio

Paul Hoffman is a crypto analyst and researcher.

Editor Bio

Hiro Kennelly is a writer, editor, and coordinator at BanklessDAO, an Associate at Bankless Consulting, and is helping to build a grants-focused organization at DAOpunks.

Designer Bio

Cosmic Clancy is a freelance illustrator and graphic artist

BanklessDAO is an education and media engine dedicated to helping individuals achieve financial independence.

Disclaimer: this isn’t investment advice. This article has been written for informational and educational purposes only and it reflects my personal experience and current views, which are subject to change.

Bankless Publishing is always accepting submissions for publication. We’d love to read your work, so please submit your article here!

Other Articles In The Crypto Basics Series

Decentralized Ledger Technology 101 by The Crypto Barista

The 101 on NFTs, A Briefing by Lanz

4 Simple Steps To Join a DAO by Samantha Marin